Trees for Human Health: Considering the Evidence

Guest post from the Washington Department of Natural Resources in coordination with the Western Urban and Community Forestry Network's #HealthyTreesHealthyLives social media campaign. Explore the hashtag #HealthyTreesHealthyLives on social media to learn more.

We have nearly 40 years of research about urban nearby nature and human health outcomes in our back pockets. But what about trees specifically and public health? Dr. Kathleen Wolf, a member of the Washington Community Forestry Council, is in the midst of a research review project that is a complex, and nontraditional collaboration.

The team and sponsors include:

- Dr. Wolf, research associate with the USDA Forest Service, Pacific NW Research Station,

- Grad student, University of Toronto sponsored by Health Canada,

- Grad student, Simon Fraser University sponsored by Natural Resources Canada, and

- Tree Fund is sponsoring a later phase, an economic valuation of benefits.

The project team is screening the extensive evidence about nearby nature and human health, estimated to be nearly 5,000 peer-reviewed articles. The first filters identified the articles that use tree measures as the variable of influence, meaning street and park trees, urban forest canopy, remote sensing indicators, and woodlands experiences.

The first filters set up a list of about 500 studies. Additional screening produced a core list of about 200. Now the detailed review is underway, but here are some preliminary observations that might help to support communications and programs concerning trees in cities:

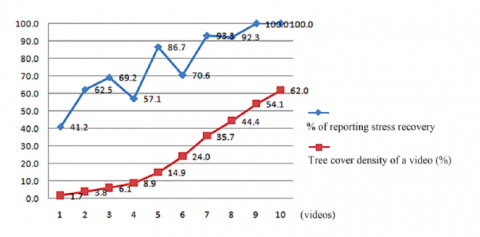

There are many sources of stress in our lives, and encounters with trees can reduce negative reactions. One study found a linear pattern of stress and anxiety recovery as scenes of urban street tree cover varied from 0-60%. This is one of the few studies to explore dose response, suggesting a human health justification for canopy goals.[1]

There are many sources of stress in our lives, and encounters with trees can reduce negative reactions. One study found a linear pattern of stress and anxiety recovery as scenes of urban street tree cover varied from 0-60%. This is one of the few studies to explore dose response, suggesting a human health justification for canopy goals.[1]

- Generally, people of higher income have greater access to health care, but trees may also be part of that equation. A study in a large city found that 11 more trees in a city block, on average, decreased cardio-metabolic conditions in ways comparable to an increase in annual personal income of $20,000 or moving to a neighborhood with $20,000 higher median income.[2]

- The general topic having the most articles is the connections between trees, air quality and asthma. The evidence is mixed; context is important. Pollen is an allergen for some people, and can worsen asthma. Yet, trees can intercept small particulates on leaf surfaces, reducing respiratory irritants. But in some urban canyons, trees can block the wind from flushing particles, actually leading to higher concentrations. Finally, tree plantings, or green screens, can buffer pollutants from major roads, protecting people in adjacent homes and schools.

To learn more, please contact Dr. Wolf at kwolf@uw.edu. Additional information about urban nearby nature and health can be found at Green Cities: Good Health.

[1] Jiang, B., Li, D., Larsen, L., Sullivan, W. C. 2016. A dose-response curve describing the relationship between urban tree cover density and self-reported stress recovery. Environment and Behavior 48, 4, 607-629.

[2] Kardan, O., Gozdyra, P., Misic, B., Moola, F., Palmer, L. J., Paus, T., Berman, M. G. 2015. Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Scientific Reports 5, 11610.